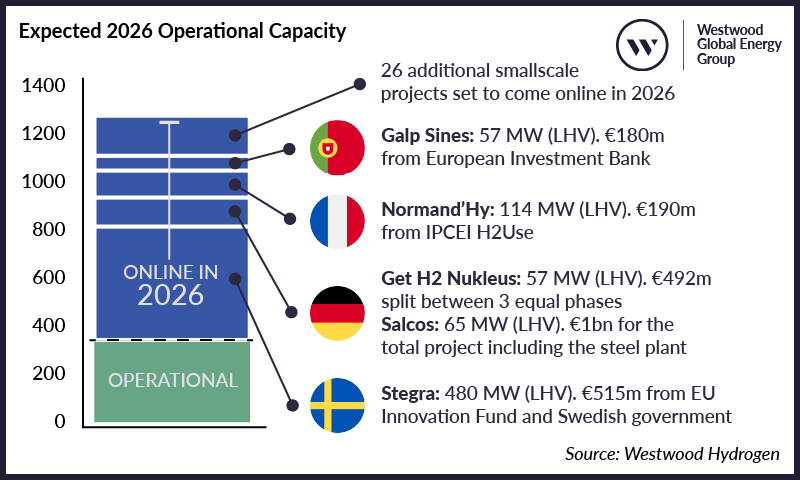

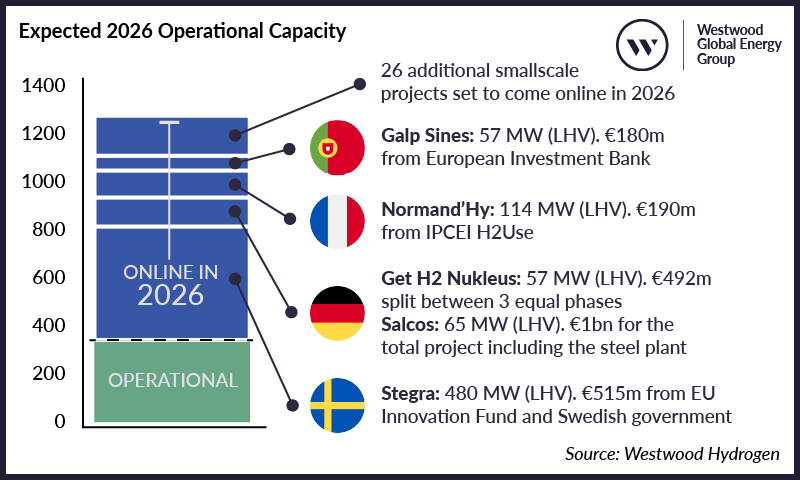

The announcement of multiple FIDs is notable in itself, but attention should be drawn to the scale of these projects. Three of the five projects boast Phase 1 electrolyser capacities of or exceeding 200MW. (Although the initial phases of BP’s Spanish HyVal match this scale, it is currently uncertain whether the FID covers the initial 200MW phases or just the 25MW first phase).

In addition to the contribution these projects will have to 2030 country and EU targets, they also help to demonstrate the industry’s scaling potential. Positive examples such as these should help to encourage other developers to advance projects in the vastly undeveloped pipeline.

Geographic diversity is another key highlight of these projects. Following the first European Hydrogen Bank (EHB) pilot auction in April, there has been a growing expectation amongst European developers that projects in the short to medium term are more likely to progress in geographic ‘sweet spots’ – countries like Spain or Portugal with abundant renewable resources and low electricity prices. However, developers are clearly finding ways to accelerate the development of projects in other markets.

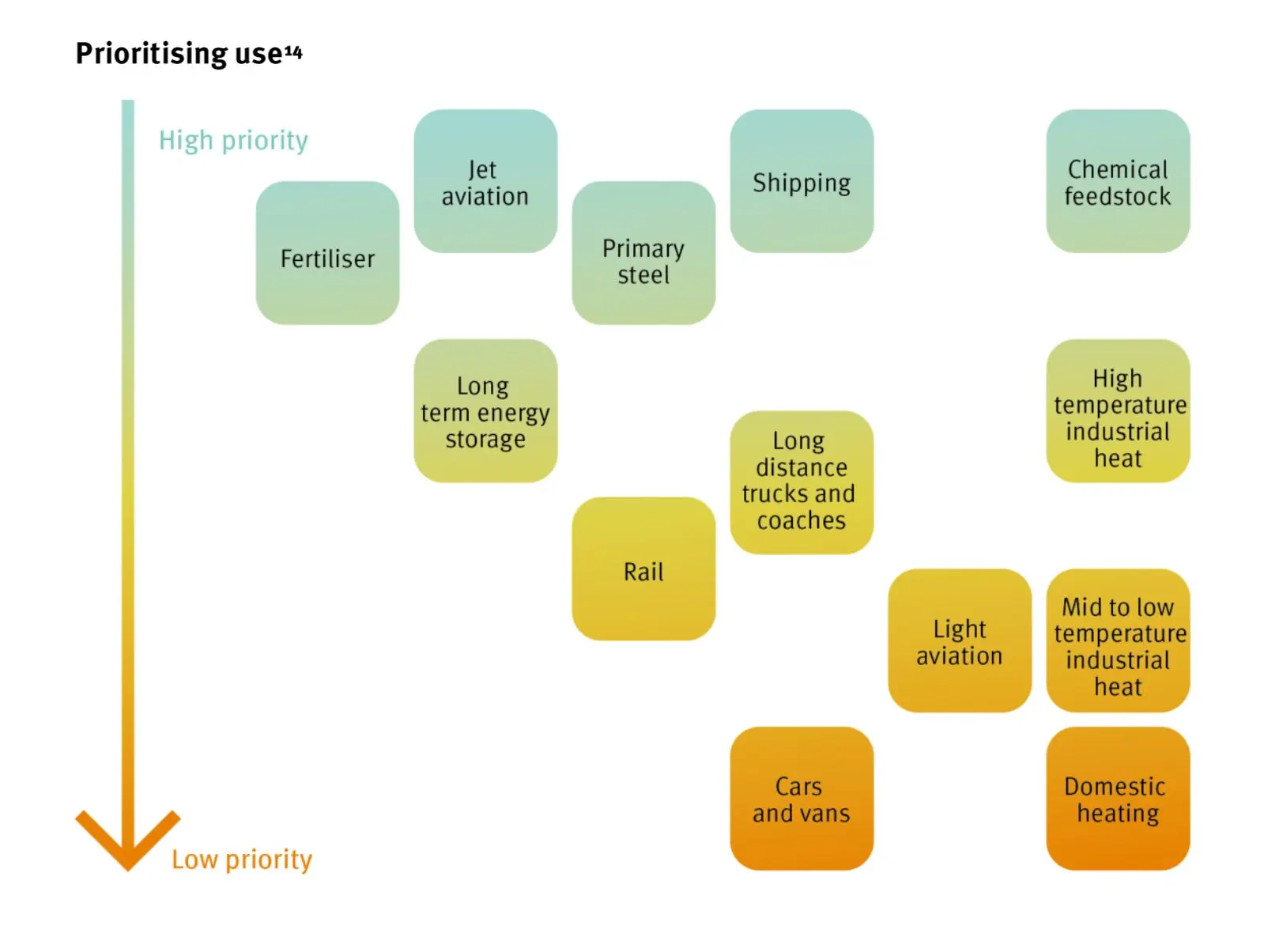

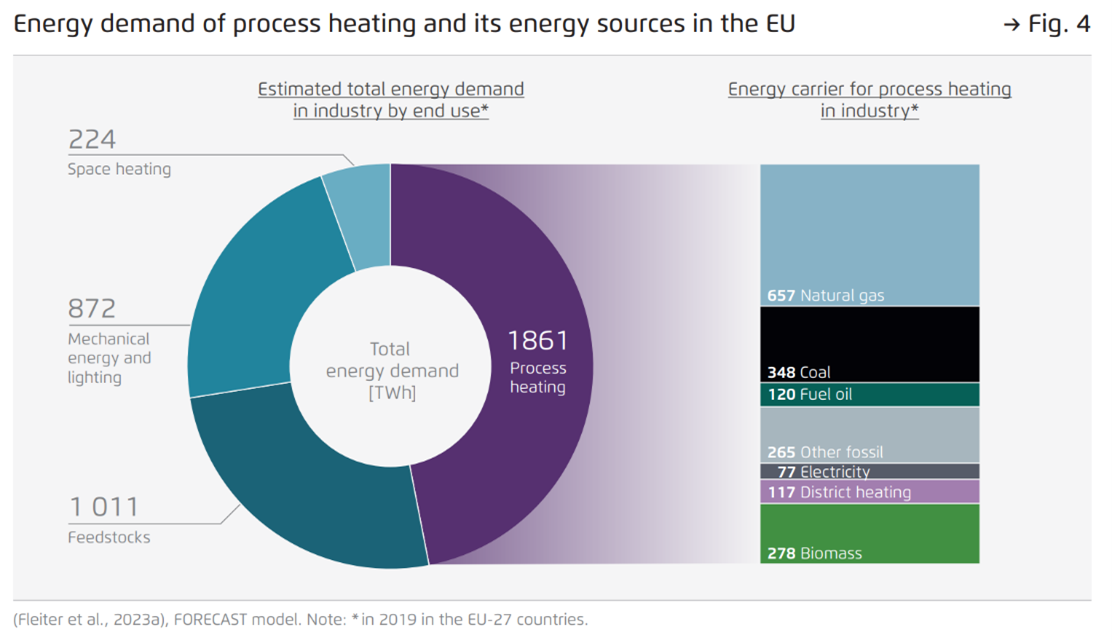

This trend may be driven by multiple factors, including the pressure on offtakers to comply with upcoming EU regulations. The EU’s Renewable Energy Directive III (REDIII) for instance, which became law in October, mandates that industries such as refining and steel source at least 42% of their hydrogen from renewable sources by 2030.

With four of the five projects targeting the decarbonisation of the developer’s or key stakeholder’s own refining or steel production assets, the strength of these mandates in accelerating project development is evident.

Furthermore, this trend could be a response to the upcoming enforcement of the ‘additionality’ clause in the EU’s rules for renewable hydrogen. Coming into force in 2028, the clause includes an exception stating that projects operational before 1 January 2028, will be exempt from these rules for 10 years.

This provides a significant advantage for developers who take FIDs in the near term, allowing them to bypass the additional cost and timeline challenges associated with building renewable capacity for each electrolytic project developed.

With four of the projects that announced FIDs last month targeting operational status before the end of 2027 – Total’s OranjeWind H2 being the only exception, targeting production from early 2028 – there will be a concerted effort from these developers to adhere to these timelines to benefit from these exemptions.

It is important to note, however, that while project developers will benefit from avoiding the ‘additionality’ requirements, they will not be able to avoid the ‘temporal correlation’ conditions, which will come into effect starting in 2030. This condition requires that hydrogen be produced in the same one-hour period as the renewable electricity generated.

Funding is a key enabler for project development, and last month saw multiple announcements, particularly from the Spanish government. Spain confirmed €794mn in state aid for seven electrolytic hydrogen projects, aiming to establish the country as a European leader in electrolytic hydrogen production. This funding, part of the Hy2Use scheme under the Important Project of Common European Interest (IPCEI), will support projects with a total electrolysis capacity of 652MW.

Spain’s second announcement underscores how funding criteria and mechanisms can facilitate continued momentum, define scaling potential, and ensure key parts of the value chain are integrated into project development. This was exemplified in July when the EU approved a new €1.2 billion auction pot for renewable[1] electrolytic projects.

Scheduled to launch in 4Q this year, developers will have 36 months to bring these projects online, with aid reduction penalties imposed for every six-month delay to the project. A clustered approach will be accepted for projects over 50MW, but individual projects must have an electrolyser capacity of at least 100MW to bid. Additionally, developers must secure an offtaker for at least 60% of the planned volumes of produced hydrogen.

While the terms of the planned auction are prescriptive, some areas raise uncertainty. Although the requirement for an offtaker is an essential component to ensure the economic viability of projects, this agreement can be in the form of agreements like a memorandum of understanding (MoU) or letter of intent (LoI).

These agreements do help to provide some certainty for the overall project, but ultimately fail to offer absolute assurance given they are non-binding agreements. Also, whereas the auction pot is exclusively for the support of renewable electrolytic projects, the government has stated that the RFNBO (Renewable Fuels of Non-Biological Origin) certification must cover at least 60% of the produced volumes, implying that 40% of the volumes could be non-renewable.

It will be crucial to monitor whether this decision to provide flexibility for developers is a move to ensure near-term progress or one that proves to be problematic in the long run.

In last month’s edition, we concluded with the idea of setting realistic expectations for the hydrogen market, and to think beyond the 2030 targets and to continue investing in and learning from periods of accelerated progress, like the one experienced in July.

This notion gained additional weight with the publication of a report by the European Court of Auditors (ECA) last month, which questioned the EU’s ‘unrealistic’ hydrogen targets. The report highlighted issues with the methodology used to establish the 10Mt production and import targets, inconsistencies in national hydrogen roadmaps, and recommended updating the hydrogen strategy and targets by the end of 2025.

However, thinking beyond these targets, maintaining accelerated progress should be the primary focus of regulators, developers, and others across the value chain. This sentiment is echoed by the EU Commission, which responded to the ECA report with concerns about maintaining investor certainty and addressing the scaling challenges that could arise from a reduction in targets.

It may be too soon to definitively call this a turning point for the European hydrogen industry. What is clearer is that thinking beyond 2030, and sustaining progress, is crucial. Ensuring continuous advancement in the hydrogen market is the reality we must strive to achieve.

Source: Jun Sasamura,, Westwood Energy